EXOA15

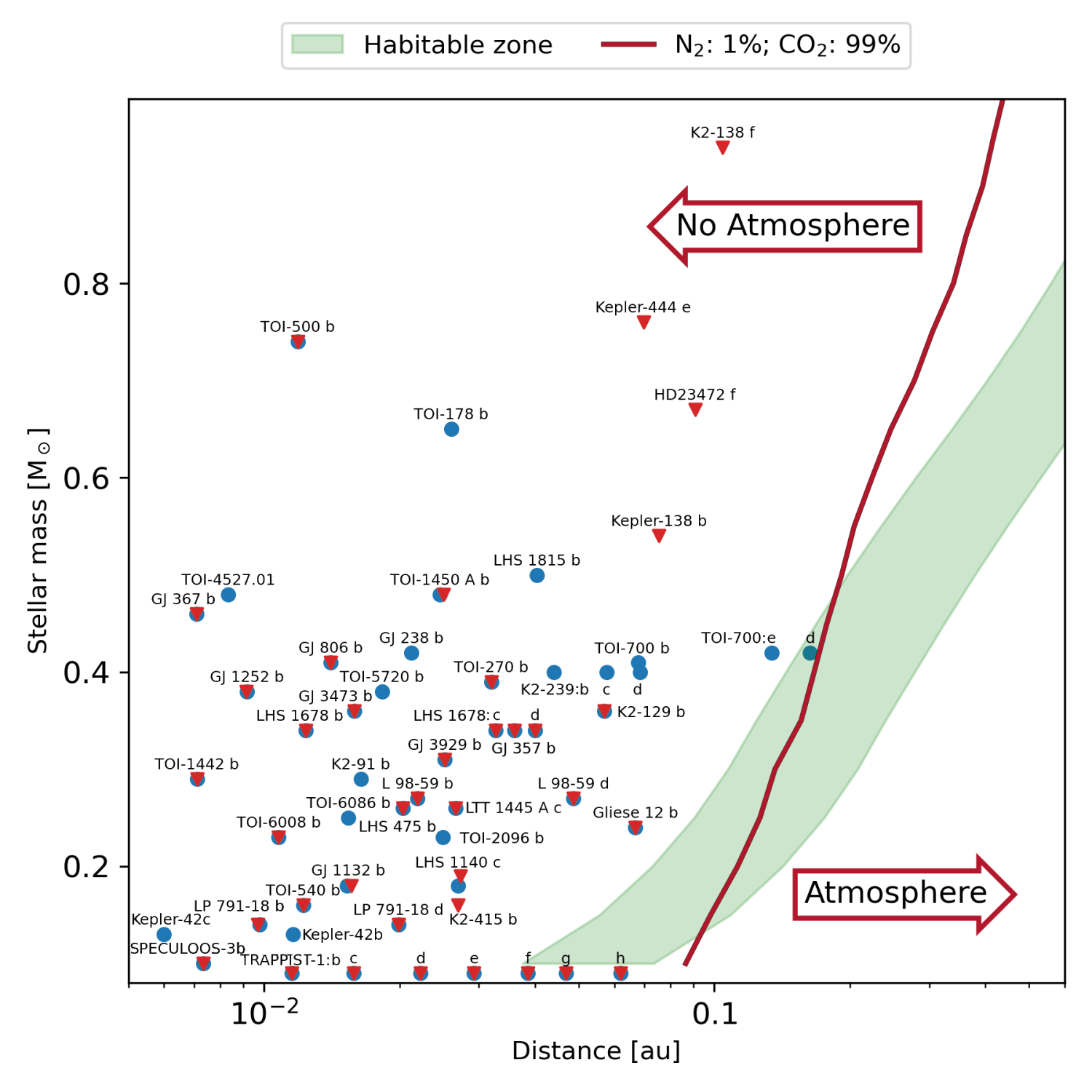

Recasting the Cosmic Shoreline in light of JWST: The Fate of Rocky Exoplanet Atmospheres

Convener:

Richard Chatterjee

|

Co-conveners:

Jake Taylor,

Claire Guimond,

Shane Carberry Mogan,

Thaddeus Komacek

Orals FRI-OB3

|

Fri, 12 Sep, 11:00–12:30 (EEST) Room Mars (Veranda 1)

Posters THU-POS

|

Attendance Thu, 11 Sep, 18:00–19:30 (EEST) | Display Thu, 11 Sep, 08:30–19:30 Finlandia Hall foyer, F221–226

* What are the strongest atmospheric constraints we can infer from transmission and emission observations?

* What are the optimal observing strategies to detect atmospheric features?

* Under what conditions can a bare rock revive an atmosphere?

* How well do we understand M-dwarf evolution, particularly X-ray flare activity over time?

* What level of ionising irradiation can drive hydrodynamic escape of metal-rich atmospheres, and how does this process depend on planetary mass?

* How will the launch of ELT, PLATO and ARIEL boost atmospheric characterisation?

We invite contributions that explore observations (both real and simulated) and models of star-planet evolution (including interior, atmospheric, and escape processes). If some of the rocky planets in the habitable zones of the galaxy’s most common stars can retain their atmospheres, the universe could be teeming with life—and astronomers just might be able to observe its signatures in the near future.

Session assets

11:00–11:03

Introduction

11:03–11:18

|

EPSC-DPS2025-37

|

solicited

|

On-site presentation

11:18–11:30

|

EPSC-DPS2025-178

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

11:30–11:42

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1043

|

ECP

|

Virtual presentation

11:42–11:54

Lessons Learned from the Hot Rocks Survey (with Erik Meier Valdés)

11:54–12:06

|

EPSC-DPS2025-952

|

On-site presentation

12:06–12:18

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1265

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

12:18–12:30

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1850

|

On-site presentation

F221

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1756

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F223

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1198

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

TRAPPIST-1 in High Resolution: Constraining Exoplanet Atmospheres Amid Systematics

(withdrawn)

F225

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1496

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

An empirical view of the Cosmic Shoreline

(withdrawn)

F226

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1609

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

Investigating the Influence of Asymmetric Error Bars on Atmospheric Retrievals

(withdrawn)